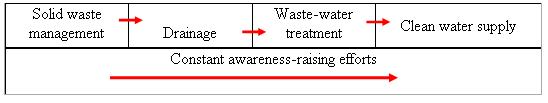

Table 1. Step-by-step approach to

environmental infrastructure

The solid waste management

phase of the project was held from 2001 to 2003. The second phase on drainage

and waste-water management started in 2004 and is planned to end in 2008. Both

phases used the same participatory approach. The first step was an educational

and communication campaign on sanitation, hygiene, and the environment. On top

of general public educational campaigns (message boards, public radio and

various activities), a specific campaign was organized for a group of village

leaders and selected activists. These activists were representatives from all

social organizations and groups of residents; they were trusted individuals in

the village.

The group of 40 activists,

who received a deeper technical training on the sanitation system over 6

weekends by the technical consultant, would later teach their own group about

the project and the sanitation service. Through the socio-cultural networks and

mass organizations, the activists could reach more than 94% of the population

through direct contact. The objective of this method was to create a core of

trusted leaders in the village that would support the project after the NGO

leaves.

The

activists and interested households had also a voice in the final planning of

the projects. Informational headquarters were set up in the community hall, and

covered each important phase of the project. Prior to finalizing projects,

public discussion was encouraged with local leaders to agree on such issues as

location of sewers, establishment of monthly fees, compulsory and optional

actions, etc.

The

waste management fees were introduced and were then gradually increased.

Currently, 80% of households in Lai Xá have joined the separation-at-source

program where the organic wastes are collected at the Composting Station. The

non-organic waste is also collected and disposed in the local landfill. The

fees are used to pay the operation and maintenance costs, as well as the

salaries of the 6 employees in charge of the service.

The

drainage and waste-water management system was much more expensive than the

solid waste treatment infrastructures. The approach for financing the second

and third phases has therefore been gradual, with households highly encouraged

to participate and contribute to the construction. A local construction

committee formed of 15 inhabitants was trained to follow the contractor’s work

and to report on the quality of the work to the village assembly. The

committee’s developed expertise was therefore useful, because its participants

could, in return, support their neighbours in the construction of their own

septic tank and the connection to the sewer. Using a committee-based approach

fostered the appropriation of this new infrastructure in Lai Xá.

By

the absence of a government institution managing the service, the village

president found an innovative way to guarantee a long-term commitment from the

households. He made each family sign an agreement that it would use the sewer

appropriately and pay the monthly fee as soon as the waste-water treatment station

would be in operation. Improper users faced local sanctions with fines on top

of having their names blacklisted at village meetings.

2. Technical

solutions

The

chosen technology was going to be low-cost and made simple for easy local

operation and maintenance. The solid waste management system in the first phase

includes manual carts for collection, covered shed for composting and open

landfill for inorganic waste. Recyclable materials are already picked up

informally by households or vendors. Compost is mainly produced through manual

mixing. The final compost is shredded, grinded and put into bags. The leachate

is treated in a sand filter bed.

In

the second phase, a combined sewerage and drainage system was chosen since it

was cheaper and since most households were already using septic tanks. The

latter help to reduce the amount of solid material in the sewer. Eight combined

sewer-overflows (CSOs) were added to avoid flooding on heavy rainy days.

Households

were taught to build their own drain, screen and grid, and connect it to the

secondary lane drainage. All new water toilets were to be completed with septic

tanks that were designed properly. Unsewered households were taught about

improved onsite sanitation: Ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines and

composting dry toilets, which were already used traditionally in the village

but were viewed as outdated and not as modern as water toilets [6].

Decentralized

waste-water treatment was planned. Six community baffled septic tanks with

anaerobic filters (BASTAF), followed by sub-surface horizontal-flow constructed

wetlands have been designed for the village six clusters. Treated waste-water

would then flow into the irrigation channels planted with aquatic macrophytes

or to the fish pond. Two waste-water treatment stations are already in

operation, serving 80 and 160 households respectively.

Figure

1. The

first Baffled Septic Tank with Anaerobic Filter (BASTAF) for 80 households in

Lai Xá.

Figure

2. The

second Baffled Septic Tank with Anaerobic Filter (BASTAF) followed by the

Horizontal Sub-surface Horizontal-flow Constructed Wetland for 160 households

in Lai Xá.

III. ACHIEVED

RESULTS

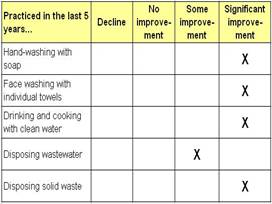

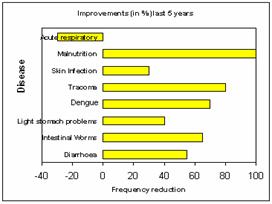

The

improvement of infrastructure and its positive impacts on the local society has

been confirmed by all interviewed villagers. Changes in hygiene behaviors and

health improvements in the village in the last 5 years have been analyzed in

2006 by Beauséjour [2] through participatory assessments (Figs. 3 and 4).

Changes in behavior were observed through discussions with woman groups while

the reductions in disease frequency were measured with consensus-reaching

interviews with local health professionals.

Figures 3 and 4. Health and

behaviour improvements measured through participative assessments [2].

Without

extra financial support, households were encouraged to improve their individual

toilets, drainage and septic tanks. Households with access to showers and

hygienic toilets (composting or water toilets) went from 25% to 60% in 5 years.

Most residents are now aware of the high level of iron and ammonia in Lai Xá

groundwater [3] and more than 80% of households now use rainwater for drinking

and cooking. Most households also agreed

to improve their waste-water drain with screen and grid chamber before

connecting to the sewer network. Visible physical improvements in the village

include: less solid waste on streets, ditches and vacant fields; reduced

flooding on rainy days; less stagnant water lying around; and more compost

available for agriculture and for resale.

Due

to the small scale of this project, it was possible to calculate the economic

benefits for the community using the WHO economist method [4]. In their

article, Hutton and Haller used a detailed economic method to give an economic

value to all potential benefits related to sanitation. Their calculations are

based on WHO statistics for each country, which we could also use if a local

(Lai Xá) value could not be determined precisely. Benefits in Lai Xá were

calculated in terms of: reduction of diarrhea, reduction in flooding, and

increased agricultural productivity. These variables were each calculated in

details terms of a savings in time, cost and health. The calculations can be

considered as being highly conservative: various water-related diseases apart

from diarrhea can be reduced with sanitation and could not be considered.

Furthermore, the assessment was made at a time when no treatment stations were

yet operational.

For

a total project cost of around 24 US$ per household per year (including all

costs related to implementation, operation and maintenance), benefits of 100

IV. DISCUSSIONS AND

CONCLUSIONS

One

main research hypothesis raised from this case study analysis is that the

leveraging of more local resources could help reduce the gap in financing for

environmental sanitation. The financial needs are actually much higher than the

current investments from combined international aid and a central Việt

Namese government. Households and communities usually present a high level of

willingness-to-pay if projects respond to local need. The second hypothesis is

that current financial resources should be increasingly invested in activities

that promote sustainability of sanitation structures, like promotion, education

and simpler technologies.

In

the Lai Xá case, the interest in maintaining cleanliness and in reusing

waste-water were key factors in encouraging participation and in promoting a

willingness-to-pay for waste-water treatment. Success of Lai Xá project has

again confirmed the need for IEC activities. IEC should be conducted in

advance, along with the other project activities, and maintained after its

completion. However, the case-study also highlights the great lack of

capacities needed to support the further decentralization of sanitation towards

local authorities.

The actor relationship

analysis in the Lai Xá project has shown that traditional socio-political

structures like social mass organizations

and user group representatives, under the People’s

Committee (PC) coordination role, are

major actors with

very significant influence on project outputs and activities [7] (Fig. 5).

Compared to other documented

rural projects, the factors that affect household contribution are much more

complex in Lai Xá. The objective is not only to make them buy a latrine, but

also to promote sustainable use and maintenance for common benefits. Household

contributions represent a promising way to reduce the financing gap in

sanitation; nevertheless, a significant portion of public resources have to be

invested in comprehensive planning, capacity-building and coordination. Central

and provincial governments still have to take leadership to support community

initiatives.

Figure

5. Example of a local management scheme.

Even in small communities

like Lai Xá, market- and demand-based approaches alone (i.e. promoting

attractive technologies and promising benefits) cannot support sustainable

access to sanitation. Urban public technologies like sewerage and common

treatment plants need comprehensive management and long-term planning. The

contributions from households are significant and should be made a priority in

order to increase the financing of sanitation.

Waste management strategies

can be adapted to local contexts by taking into consideration such things as

natural conditions, financial affordability, social acceptance, and local

business needs. Household-centered approaches, decentralized technologies, and

low-cost waste-water treatment processes, have been found to be the most

appropriate for the Vietnamese rural and peri-urban areas like Lai Xá.

REFERENCES

1. Beauséjour J., Nguyen V.A., 2007. Decentralized sanitation implementation in Việt

2. Beauséjour J., 2008. Alternatives to centralized sanitation in

developing countries: the case of peri-urban areas of Việt

3. Büsser S., Pham Thuy Nga, Morel Antoine, Nguyen

Viet Anh, 2007. Characteristics and quantities of

domestic waste-water in urban and peri-urban households in Hà Nội.

J. CEETIA News, 1.

4. Hutton G., Haller L., 2004. Evaluation of costs and benefits of water and

sanitation improvements at the global level. WHO,

5. Mara D., Drangert J. O.,

Nguyen V. A., Tonderski A., Gulyas H., Tonderski K., 2007. Selection of sustainable sanitation

arrangements. J. W. Policy, 9

: 305-318.

6. Nguyễn V.A., 2007. Septic

tank and improved septic tank. Construction

Publ. House, Hà Nội (in Vietnamese).

7. Nguyễn V.A,

Morel A., Trần H.N., 2008. Decentralized approach to waste-water management:

A true potential for Việt

8. Rural Water Supply and Environmental Sanitation,

2008. Journal of the National

Centre for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation (NCERWASS), 2 : 5-8 (in

Vietnamese).

9. World Bank, 2004. Việt